|

BAA instrument no.

93 R.

A. Marriott Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 116 (6) (December 2006),

299–305 |

|

Instrument no. 93 has

been in almost continual use for more than a hundred years. Since it left the

workshop of its maker, George Calver, it has kept company with several other

notable instruments and has been used by many eminent astronomers. It was

added to the Association’s collection in 1945. Instrument no. 93 is a 12¼-inch [1] reflector made

by George Calver more than a century ago. Its lines are reminiscent of the

blunt naval architecture of the period, and there is even a touch of Old Empire,

for tucked away at the base of the RA drive housing, and substituting for a

washer, is a pierced and worn Indian coin dated 1909. The Rev T. E. R.

Phillips used the telescope for double-star and planetary observations for

thirty-five years, until his death in 1942; from 1947 to 1962, F. M. Holborn

used it to add significantly to the store of observations maintained by the

Variable Star Section; in 1963 it passed to A. W. Heath, who conducted

planetary work with it for thirty-four years; in 1997 it was placed on loan

to R. M. Steele; and now it has a new home. |

|

George Calver The instrument’s maker,

George Calver (1834–1927), produced his first mirror in the mid-1860s. Around

1850 he had moved from Walpole, Suffolk, where he was born, to Great

Yarmouth, Norfolk, where he worked in the boot and shoe trade for several

years. While living in Yarmouth he became acquainted with a Rev Matthews.

Nothing is known of Matthews (he may have been a dissenting minister,

excluded from Anglican records) except that he had acquired a telescope with

a mirror by G. H. With – who made his first mirror in 1862 – and

challenged Calver to make a mirror of equal quality.[2] Calver rose to the challenge,

and thereafter devoted the rest of his life to the production of instruments.

By about 1870 he had moved to Widford, near Chelmsford, and in 1904 he

returned to Walpole, where he continued his work into old age. Throughout

his long career Calver maintained a business with several employees, and

reputedly produced several thousand instruments, including mirrors either

made or refigured.[3] Although he designed the stands they were made by T.

Lepard and Sons, of Great Yarmouth, and he was not averse to attaching his

name to the work of others if he was involved. He published several editions

of his small book, Hints on Silvered

Glass Reflecting Telescopes – which, in addition to illustrations

of the various telescopes and mounts, included many testimonials from

satisfied customers worldwide – and he accepted orders for instruments

of any size. His output included a 20-inch for James H. Worthington, a

24-inch for the Royal Observatory Edinburgh, a 15-inch and a 30-inch for C.

R. d’Esterre, and an 18-inch and a 37-inch for Andrew A. Common. He

afterwards made another 37-inch for Common, and the complete instrument later

passed to Edward Crossley, of Halifax. (In the early 1890s, Crossley

presented it to the Lick Observatory, California.) Calver’s

largest mirror was a 50-inch, made for Sir Henry Bessemer in 1884. Bessemer

apparently devised what he thought was a cheap and simple way of producing a

paraboloid which Calver agreed to try, but the mirror was not a success.

Calver would no doubt have produced an excellent 50-inch mirror by his normal

techniques. He was not daunted by the manufacture of large optics, and around

the same time, when James Lick offered a prize for a mirror of record size,

he quoted for a 96-inch. Calver

was very much involved with the astronomical community. Besides being a

factor of instruments he was also an observer, and contributed numerous

articles and letters to English

Mechanic. He was an Original Member of the Association (those who joined

before the end of 1890), and served on the Provisional Committee that

confirmed the name of the new organisation and established its first Council. Calver

died on 4 July 1927,[4] three weeks before his 93rd birthday, and his wife

died, aged 95, a year later. His gravestone in Walpole churchyard records

that he was ‘Kind to the poor and little children’, but does not

refer to his life’s work. The

eminent optical practitioner Horace Dall [5] – whose first sizeable

telescope was an 8½-inch Calver – corresponded with Calver in

1923, and in 1952 he visited Walpole. The workshop where many mirrors were

made still survived, and notes on the progress of telescopes built early in

the century were still marked on wall panels, while elderly residents of the

village related details of Calver’s early life not otherwise

recorded.[6] Dall was born in 1901 in Chelmsford – only a few miles

from Widford, where Calver had lived until 1904. T. E. R. Phillips Theodore Evelyn Reece Phillips

(1868–1942) was born at Kibworth, Leicestershire, and was educated at

Yeovil Grammar School and St Edmund Hall, Oxford. After his ordination in

1891 he was appointed to a curacy at Holy Trinity, Taunton, and from 1895 to

1901 was curate at Hendford, near Yeovil. In 1901 he moved to the parish of

St Saviour, Croydon, married Mellicent Kynaston five years later, and moved

to Ashtead, where he held his last curacy from 1906 to 1916. He was then

inducted as rector of Headley, Surrey, where he remained until his retirement

in 1941. Phillips’

extensive services to the Association began when he became a member in 1896.

He contributed observations over a period of forty-five years, and was

Director of the Jupiter Section 1901–34, Director of the Saturn Section

1934–39, and President 1914–16. He also devoted a great deal of

his time to the work of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1899 he was

elected a Fellow, he served as one of the Secretaries throughout

1919–25 and as President during 1927–29, and was a member of

Council, with only two short intervals, from 1911 until 1942. In addition, he

was a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society. His first scientific

interest had been meteorology, and his observations included an unbroken

record of rainfall and temperature throughout the entire time that he lived

at Headley. He also spent time in the pursuits of sketching, botany, music

and cricket; and, of course, had the responsibility of parochial duties and

commitments. During the 1920s he was also involved in |

|

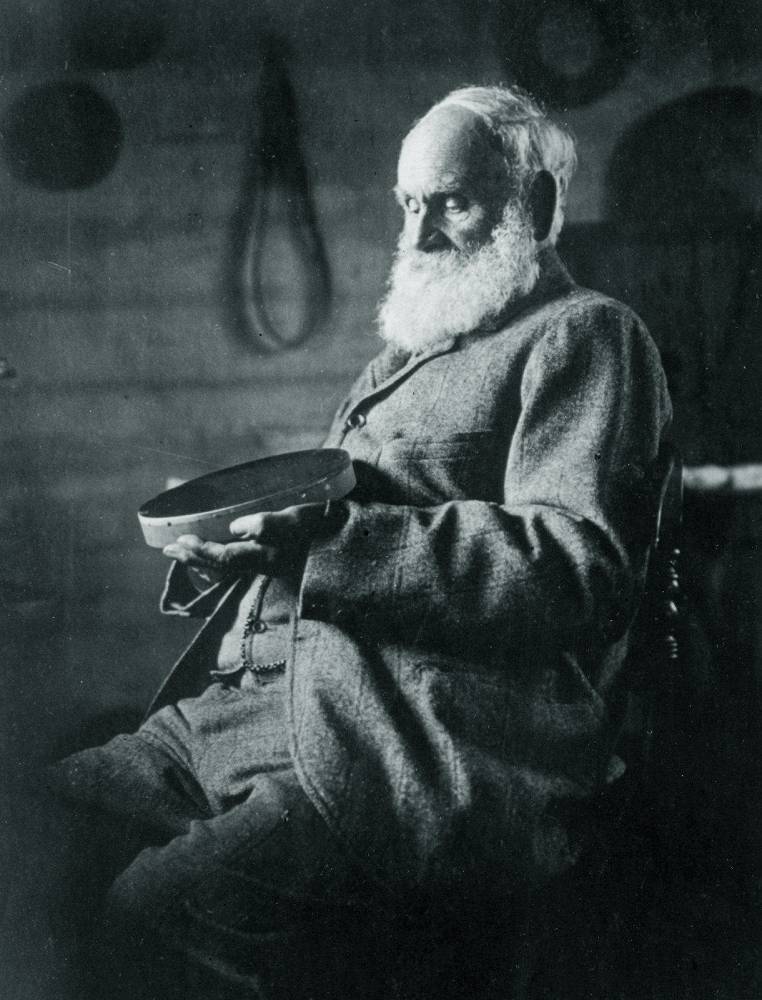

George Calver (1834–1927),

aged about 80. He is holding a 10-inch mirror, believed to be the one made

for the Rev MacKinnon of Newport, Isle of Wight, who took the photograph

about 1914. McKinnon died in 1940. This photograph – originally

published in English Mechanic

– was presented to the Royal Astronomical Society by W. H. Steavenson; but

its quality is superior to the reproduction in that magazine, and so he may

have acquired it elsewhere. (RAS MS Steavenson 1 Item 2.)

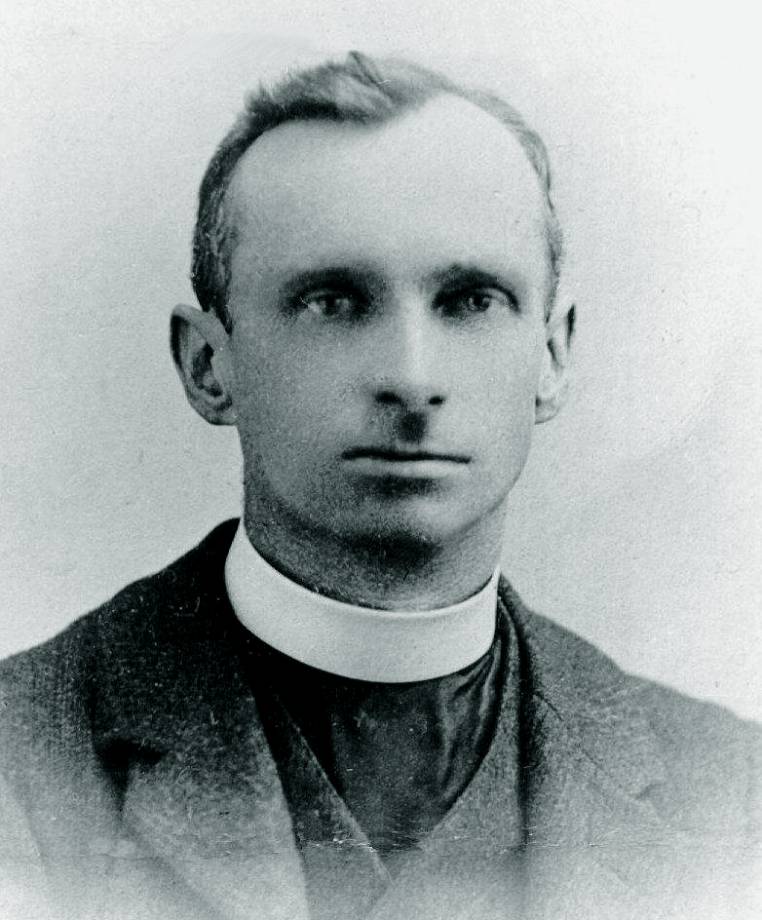

Rev Theodore Evelyn Reece

Phillips (1868–1942). (RAS MS Phillips 5B No. 14; © Parish of

Headley.) |

|||||

|

the preparation and delivery, in

various parts of the country, of courses of University Extension Lectures, represented

the Church of England on international committees, and throughout

1925–35 was President of Commission 16 of the International

Astronomical Union, dealing with all matters pertaining to the observation of

planets and comets. At

about the time that Phillips left Taunton in 1895 he was given a 3-inch

refractor. Soon afterwards he acquired a 9¼-inch reflector with a With

mirror, with which he began a systematic study of the planets, and over the

ensuing decade he regularly contributed observations to the Jupiter and Mars

Sections. He acquired the 12¼-inch Calver in 1907. Towards

the end of the nineteenth century, Calver’s price for a 12½-inch

mirror (his lists do not include a 12¼-inch) was £38 10s, the

appropriate flat was £4 15s, eyepieces were priced around

£1–2, and a complete instrument of the size and type owned by

Phillips was £240. However, in the five issues of the

Association’s Journal from

November 1906 to March 1907, the advertisement of W. Watson and Sons, of High

Holborn, London, includes a second-hand reflector ‘with 12¼-inch

mirror, by Calver, mounted on an equatorial head and iron pillar, divided

circles, eight eyepieces. Complete, in perfect condition. Price,

£50.’ This description exactly matches instrument no. 93, and the

Jupiter Section Memoirs indicate

that Phillips was using his 9¼-inch into 1907 and the 12¼-inch

from towards the end of that year. In 1906 he had the 9¼-inch mirror

refigured by Calver and was perhaps impressed with the result; and in the

same year he moved from Croydon to Ashtead, with possibly an increase in his

income. Curates’ stipends varied considerably, and at that time the

average was about £120 per annum. Assuming this to be Phillips’

salary – and perhaps his only means – a full-priced

12¼-inch Calver would have cost him two years’ income. He may

well have taken advantage of Watson’s offer, but even at £50 it

was not inexpensive. If it was the same instrument, then its earlier

provenence will never be known, as the advertisement did not reveal the

source; and as Calver had described and offered ‘The New Form of No. 2,

or Column Stand’ as early as 1880, it might previously have been used

for many years. |

|||||||

|

Phillips

used the 12¼-inch primarily for observations of Jupiter, Mars, comets and

double stars, and it was later joined by several other notable instruments.

In 1911 William Coleman (1824–1911), of Dover, bequeathed an 8-inch

Cooke refractor to the Royal Astronomical Society.[7] Together with its

observatory, it was immediately placed on loan to Phillips, and over the

ensuing thirty years it was used primarily for double-star work and also for

planetary observations. In 1917 the Association’s 18-inch With mirror

[8] (instrument no. 3, presented by Nathaniel E. Green in 1897) was also

entrusted to him, and was set up on an English equatorial mount, in the open

near the observatories, specifically for use by members of the Association.

Ten years later it took the place of the 12¼-inch on the Calver mount. One of the

regular visitors to Phillips’ observatory was Reginald L. Waterfield

(1900–1986).[9] In 1914 Waterfield had taken up J. H.

Worthington’s offer to BAA members to use his private observatory at

Four Marks, near Winchester [10] – an observatory equipped with several

instruments, including a 20-inch Calver reflector (noted above) and a 10-inch

Cooke refractor (later acquired by Walter Goodacre, and now at the Mills

Observatory, Dundee). In 1916 he was given the use of the 6-inch Cooke

refractor at John Player’s observatory in Cheltenham, and after the war

he began to visit Headley. After qualifying at Guy’s Hospital, London,

in 1925, he spent two years at Johns Hopkins University Hospital, Baltimore,

and on his return to England he moved to Headley in 1930. Shortly afterwards

he erected a third building at the observatory to house the 6-inch Cooke

refractor – bequeathed to him by Player – and two years later

augmented the equipment with photographic lenses by Cooke and Aldis,

spectroscopic equipment, and several subsidiary instruments. Player’s

bequest included a transit instrument and a sidereal clock, both by Cooke,

and the transit instrument was set up to replace the 2-inch transit

instrument by Dollond which Phillips had had on loan from the Association

from 1907 to 1929 (instrument no. 4, presented by Tyson Crawford –

senior partner at Dollond’s – in 1898). Waterfield was Director

of the Mars Section from 1931 to 1942, and throughout this period the planet

was observed with the 8-inch Cooke refractor and the 18-inch With reflector

(on the Calver mount). These two instruments were generally used at the same

time – one by Phillips and one by Waterfield – while the 6-inch

Cooke and its equipment was used for photography of comets, nebulae and

star-clouds. Basing

his main line of research upon the pioneering work of A. Stanley Williams

[11] (who had used a 6½-inch Calver), Phillips made more than 30,000

determinations of the longitudes of spots and markings on Jupiter, maintained

a regular series of measurements of the latitudes of the belts, and produced

numerous drawings. At every opposition of Mars he contributed a wealth of

notes and drawings, and his attention was divided only if the two planets

were favourably situated at the same time. His first BAA Presidential Address

was a summary of the surface features of Jupiter and the rates of drift of

the currents in different latitudes, and in his second Address he presented

the results of his analysis of the light-curves of eighty variable stars.

During his tenure as Director of the Jupiter Section (1901–34) and for

five years afterwards, he produced twenty Section Memoirs,[12] although during 1934–39 he produced no Saturn

Section Memoirs [13] (which was not

unusual for the Section). He was also an assiduous observer of double stars,

and published several lists of micrometric measurements [14] produced with

the Calver and the Cooke. In 1940, after

an operation and several weeks in hospital, Phillips decided to retire, and

in January 1941 he moved to Walton-on-the-Hill, about three miles from

Headley, from where he was able to visit his observatories occasionally.

Waterfield made arrangements to rent the observatory field and to carry on

the observatory on the same site, and also conjectured that ‘a more

detailed account of the major equipment and of the work done with it will be

contributed to a future number of the Journal by Mr

Phillips.’[15] However, Phillips died on 13 May 1942, and the proposed

report was never published. Phillips’

contributions to astronomy were officially recognised by three awards. In

1918 the Royal Astronomical Society awarded him the Hannah Jackson

(née Gwilt) Gift and Medal; in 1930 he was the first recipient of the

Association’s Walter Goodacre Award;[16] and on 28 February 1942

– less than three months before his death – Oxford University

conferred upon him the degree of DSc honoris

causa. Soon

afterwards, Bertrand M. Peek (his successor as Director of the Jupiter

Section) wrote of Phillips’ immense influence: ‘It is not

surprising that to so many amateurs in the British Isles the planets should

have seemed to revolve around Headley, where there was always the kindest and

most genuine welcome awaiting any inquirer into the mysteries of the heavens,

were he the veriest tyro, eager for his first glimpse through a telescope, or

the serious worker, come to share the rigours of an all-night session, and

where both alike were sure to be infected with some of Phillips’

boundless enthusiasm... And who, from Astronomers Royal and learned

Professors to the humblest owner of a 3-inch refractor... will forget the

genial atmosphere and the eager welcome accorded them? In the Visitors’

Book of the observatory are to be found the signatures of many distinguished

astronomers from all over the world.’[17] Despite

Phillips’ longstanding and extensive service he did not bequeath

anything to the Association, and it was some time before his instruments

moved on. During this interim, the most lively activity in that peaceful

Surrey glebe was probably the occasion in 1944 when a German flying bomb

landed and exploded nearby. The observatories suffered some damage, but the

instruments survived intact. In

1945 the Association’s 18-inch With mirror was placed on loan elsewhere

(and, several borrowers later, is still in use); in the same year the

Association purchased the 12¼-inch Calver, together with a 3-inch

refractor by Hudson, from Mrs Phillips, and in 1947 both were placed on loan

to F. M. Holborn;[18] in 1948 Waterfield moved his observatory and his 6-inch

Cooke refractor to Ascot, Berkshire;[19] and in 1950 the Royal Astronomical

Society sold the 8-inch Cooke, with two spectroscopes and a micrometer, for

£800, to the Port Elizabeth Centre of the Astronomical Society of South

Africa.[20] F. M. Holborn Frank Maurice Holborn

(1884–1962) joined the Association in 1925. His name first appeared on

the Council list in the 1932–33 session, and he served on Council

– including as Secretary (1939–46) and President (1946–48)

– for most of the ensuing thirty years.[21] |

|

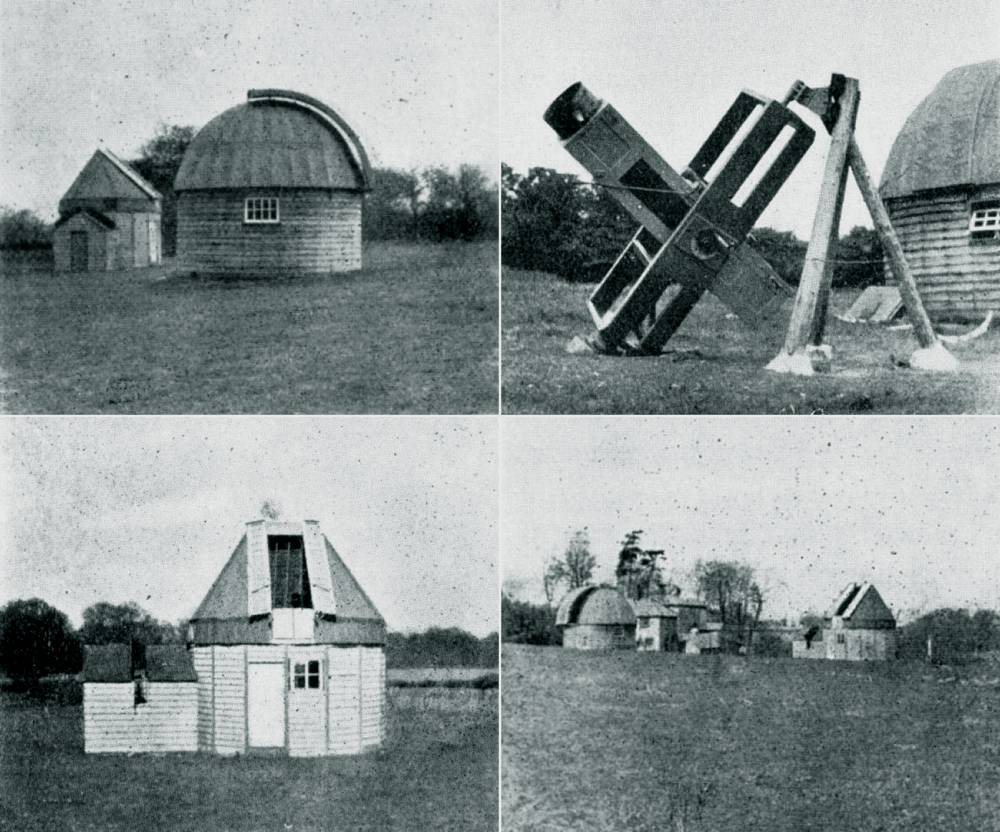

The

observatories at Headley in the early 1920s. The domed building houses the

12¼-inch Calver, while the conic-roofed Romsey-type observatory, with

a transit room, houses the 8-inch Cooke. The instrument at top right

incorporates the 18-inch With mirror (instrument no. 3). (Photographs by W.

H. Steavenson.)

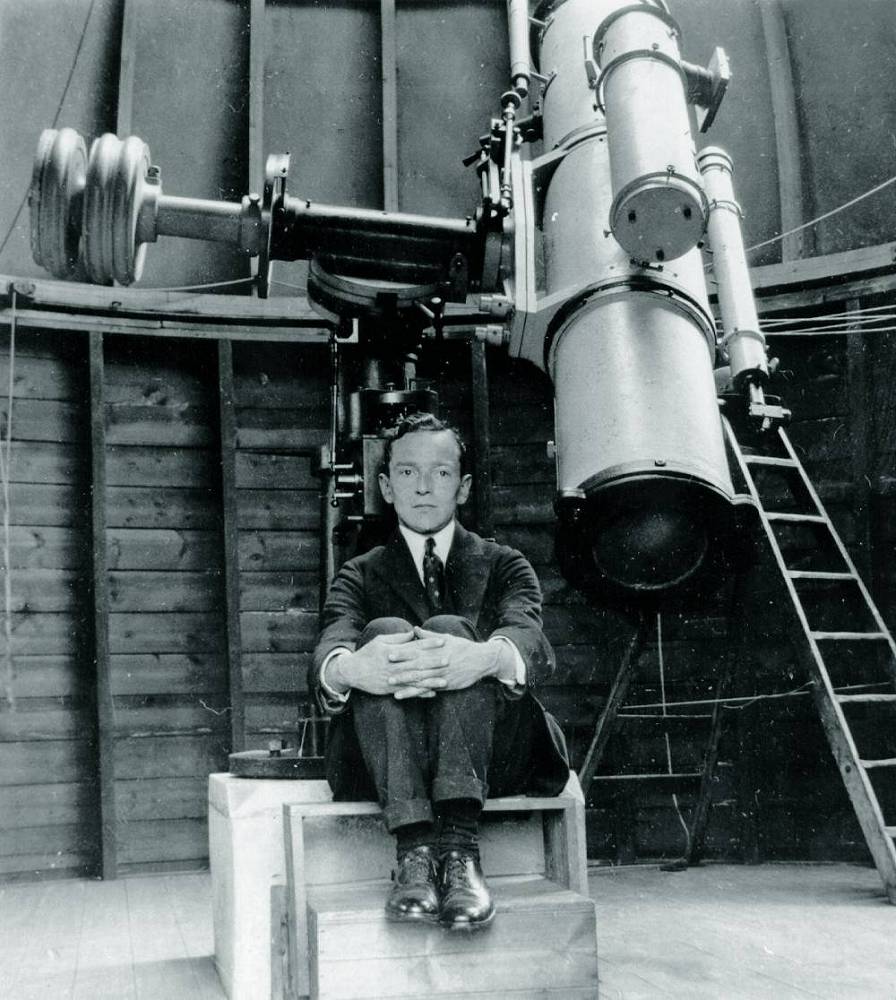

Frederick J. Hargreaves perches

in front of the 12¼-inch Calver at Headley, c.1930. Hargreaves (1891–1970) joined the Association in

1923, served as Director of the Photographic Section 1926–37 and

President 1942–44, and was recipient of the Royal Astronomical

Society’s Hannah Jackson (née Gwilt) Gift and Medal in 1938 and

the Association’s Walter Goodacre Award in 1959. This photograph was

taken during one of Phillips’ Annual Visitations held in the 1920s and

1930s. Other photographs of these gatherings include Walter Goodacre, Gerald

Merton, Leslie J. Comrie, Rev Dr Martin Davidson, R. L. Waterfield, W. H.

Steavenson, A. C. D. Crommelin, H. P. Hollis, F. J. Sellers, Sir James Jeans,

Sir Frank Dyson, Sir Harold Spencer Jones, and many other eminent names. (RAS

MS Phillips 5B No. 9; copyright Parish of Headley.)

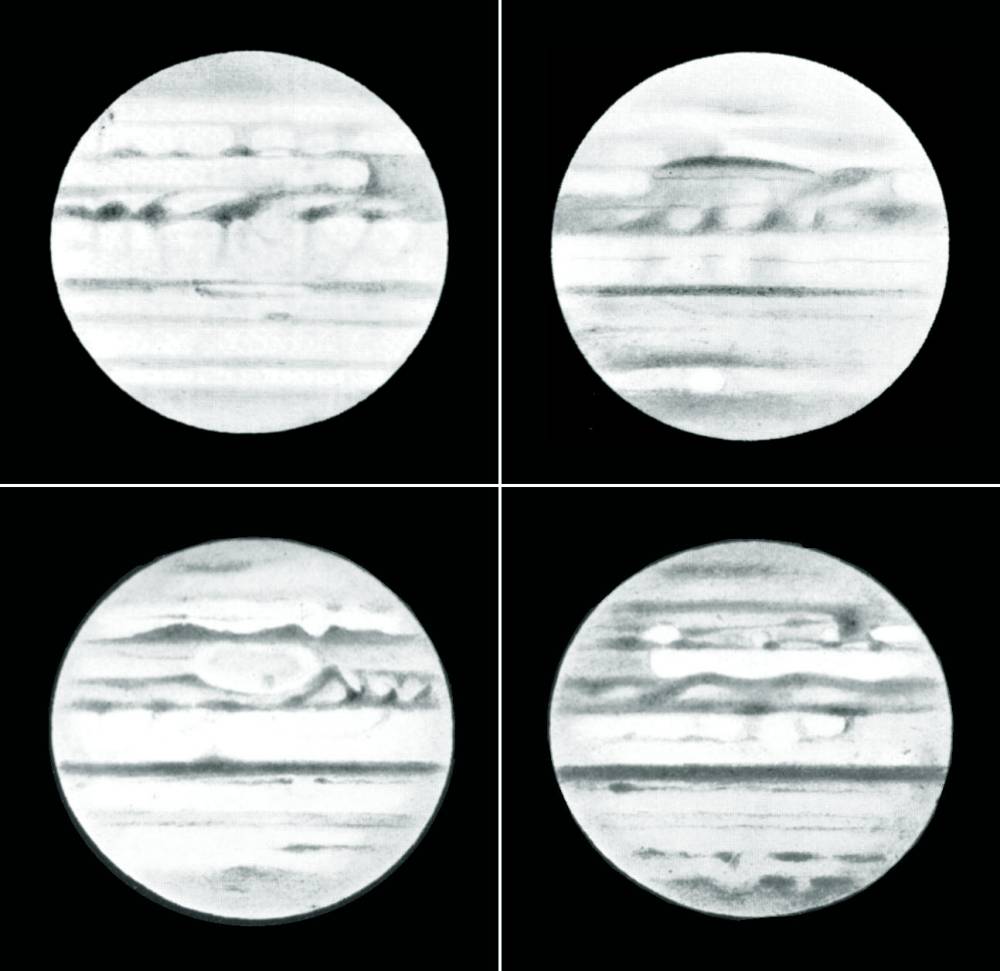

Four of

T. E. R. Phillips’ drawings of Jupiter, made with the 12¼-inch

Calver: (upper) 1908 April 14, 0655 GMAT; 1909 April 15, 0715 GMAT; (lower)

1910 March 14, 1245 GMAT; 1910 March 29, 1325 GMAT. |

|||||

|

Immediately

on joining the Association Holborn began to regularly submit observations to

the Variable Star Section. He already had a 3½-inch Wray refractor, a

2-inch refractor and binoculars, and in 1926 he acquired an 8½-inch

Calver reflector (made in 1884). The 2-inch refractor was home-made, the

object-glass of crown and flint being ‘married up by Dr Steavenson from

a choice of a few dozen such found by him in a junk shop selling ex-army

stuff after the last war. The telescope body is of wood... The rack mount

(from a magic lantern) was found in a pawnshop... the dew-cap is a cocoa

tin.’ These instruments constituted his observatory in Streatham, and

were all used regularly for many years.[22] In addition, from 1934 to 1937 he

also had use of the 3½-inch Wray refractor bequeathed to the

Association by Elizabeth Brown in 1899 (instrument no. 6). In

1935 the Variable Star Section Chart Committee was formed, and Holborn was

entrusted with the selection of stars for the new comparison star sequences,

checking the adopted magnitudes and vetting the charts before official

acceptance and issue. Innumerable hours were spent at the eyepiece on this

work alone, and it often interfered with his own observing programme. He

considered that ‘the job I shall never see finished is the revision of

sequences; so much vetting at the telescope remains to be done, and that must

be unhurried.’ The

12¼-inch Calver was placed on loan to Holborn in 1947 – during

his term as President, and in the same year that he and Waterfield, and many

others, attended a service for the dedication of a memorial to Phillips in

Headley church [23] – and on his retirement from the dental profession

in 1950 he moved to Peaslake and supplemented his equipment with a 5-inch

Ross refractor [24] (which he later bequeathed to the Association –

instrument no. 237). A highly experienced observer with notable acuity of

vision, he contributed about 40,000 observations of variable stars, and also

carried out solar and planetary work. In 1952 he received the Walter Goodacre

Award in recognition of his observational work and his service on Council. The

Calver would no doubt have enabled Holborn to extend his observations to

fainter magnitudes. Unfortunately, on one occasion (some time during the late

1950s) the telescope accidentally rotated upside down, and the mirror –

which at that time did not have a retaining ring above it – fell down

the tube and was broken. Soon afterwards, a new mirror (an 11¾-inch)

was supplied by Henry Wildey. A. W. Heath In 1963 the instrument was placed

on loan to Alan Heath, and on 7 May it was delivered to his home in Long

Eaton. The instrument appeared to be in generally poor condition, and he

therefore decided to completely refurbish it. In order to accommodate the

telescope some alterations to his observatory were necessary, and this task

was completed on 25 July. The first observation – a fine view of Saturn

– was made on 8 September. The

following year Heath was appointed Director of the Saturn Section, and the

telescope was in regular use by him – mainly for planetary observations

– until 1997. Lunar work was also undertaken, and solar observations

were made with a 2-inch Broadhurst Clarkson refractor mounted on the main

telescope. Observations were contributed to several BAA Sections, and

students from evening classes and youth groups, besides any interested

persons, were also afforded an opportunity to see the night sky through a

large telescope. On

relinquishing the Calver, Heath acquired a 10-inch reflector by Cave and an

8-inch Schmidt–Cassegrain, and built a new observatory. He said of the

Calver that it had been ‘both a privilege and an honour to have had the

use of a telescope with such an impressive history and provenance.’ |

|

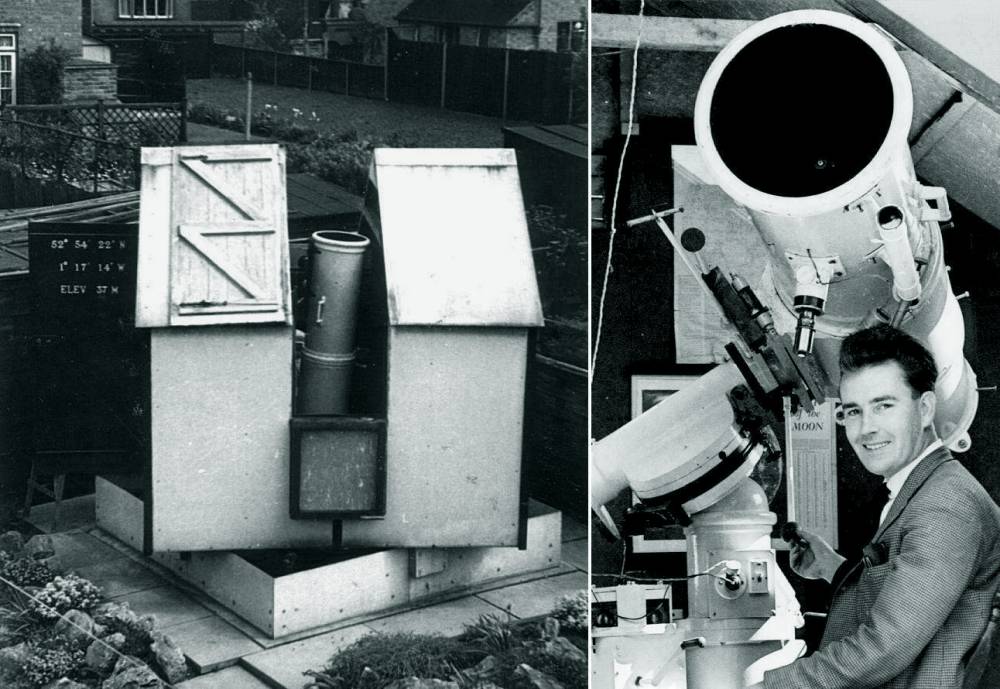

F. M.

Holborn. (Courtesy Dr R. F. Griffin.)

A. W.

Heath and his observatory at Long Eaton, 1963. (Courtesy

A. W. Heath.) |

|||||

|

Conversely,

with Heath the instrument had been in very capable hands. He joined the

Association in 1953, served as Director of the Saturn Section 1964–70

and 1975–93, was Acting Director of the Solar Section 1988–89,

and was recipient of the Walter Goodacre Award in 1986. R. M. Steele Robert Steele first became

acquainted with the instrument in the late 1960s, when as a teenager he saw

two photographs of it – one of them including Alan Heath – in

James Muirden’s Amateur

Astronomer’s Handbook. Fortuitously, when he applied for the loan

of an instrument in 1997 it happened that Heath wanted to relinquish the

Calver, as he was moving house and had already dismantled his observatory.

The telescope was collected on 21 June. It required the efforts of five men

to lift the equatorial head into the van, and by the time the rest of the

components were loaded the vehicle’s suspension was almost bottomed.

The telescope was then transported to its new home in Leeds. During

one weekend in August 1997 it took several volunteers quite some time to

rope-haul the pedestal, on wooden boards and rollers, across Steele’s

garden. All the parts were then stripped and repainted, Peter Drew overhauled

the clock and restored the rotation of the tube (which had become jammed),

and the original focuser was replaced with a more servicable rack-and-pinion

mount (also supplied by Drew) in keeping with the instrument. On

12 October the disassembled mounting was lubricated, sixty-three new

½-inch ball bearings were inserted in the equatorial head, and work

began on the reassembly of the telescope. The process of remounting the steel

tube and fitting the three massive counterweights required three people. In

mid-November, after the repair of a pivot pin on the RA drive worm housing,

the slow motions were fitted. According

to an inscription on the back of the mirror it is pyrex, with a focal length

of 78 inches (f/6.6). However, it was determined that it too required work,

and after obtaining permission it was refigured (to the same focal length)

and aluminised by Jon Owen. On 30 November, Peter Drew trialed it with the

new focusing mount; and all was finished. The

instrument was used to some extent, but Steele eventually succumbed to

temptation and purchased a Schmidt–Cassegrain. At this point, the Calver

had to be accommodated elsewhere. Specifications The majority of the instrument is

original, and bears the marks of fittings that have been added and removed

over the years. The Wildey mirror has been refigured, the secondary mirror

(2½-inch minor axis) attaches to a four-vane spider, and the finder is

a 1½-inch f/10 brass refractor. The

instrument is accompanied by a wooden box containing seven old RAS-thread

eyepieces. On the lid of this box is written ‘BAA eyepieces from

Headley, 1946 Nov 1’, and stuck to the inside of the lid is a piece of

paper with pencilled notes. There is no signature, but as the instrument had

by then been acquired by the Association they were probably written by J. H.

J. Burtt (Curator of Instruments, 1946–48). Unlike the eyepieces, the

comments in the note are illuminating. For example: ‘3, v milky’

Cooke orthoscopic; ‘5, almost opaque & useless’ Tolles;

‘6, not really 1/5, more like 1/3, v bad ghost’; ‘7, full

of blemishes: hopeless glass’. The top of the bakelite barrel of no. 5

is inscribed ‘F = 0.328, H. E. Dall 1931’. The

steel tube has an internal diameter of 13¼ inches, and is 81 inches

long without the primary cell. It rotates in a sleeve, incorporates a door

for access to the mirror, and is crowned with a distinctive broad-flanged

steel ring that counterbalances the massive primary mirror cell and could

also be used for the attachment of subsidiary equipment, The

equatorial head is comprised of three separate steel discs. The bottom and

central discs have central perforations, while the upper disc has the RA axis

spindle attached. The bottom disc is fixed to the head and contains the

½-inch ball bearing track. The central disc is bound with the brass RA

drive circle/setting circle, and also contains two countersunk square-headed

bolts, set 120° apart, which penetrate to about two thirds the radius of

the disc. Tightening or releasing the bolts normally locks or releases the RA

circle by mechanical deformation of the steel core of the RA drive circle. A

small sprocket and spindle attached to the lower disc meshes with a

straight-cut gear track on the brass RA drive circle, to enable movement of

the RA setting circle in relation to a pointer fixed to the upper disc. The

upper disc casting contains the declination axis sleeve as well as the RA

axis spindle. The

head is supported by a 28-inch wide cast iron bell-foot pedestal, levelled by

three bolts. A mounting plate for the driving clock bolts to the north side

of the pedestal 23 inches above ground level. The clock drive consists of a

heavy steel case containing a ratcheted winding mechanism surmounted by a

centrifugal governor braked by a brass friction ring, and movement is

provided by descending weights attached to the winding gear by a steel wire.

The design calls for a pit beneath the pedestal for the weights, with the

wire passing through a slot in the foot of the pedestal. The manual slow

motions in RA and declination are operated through rods provided at the

eyepiece end of the tube, and RA and declination are graduated on 12-inch

brass-bound circles. The combined pedestal and equatorial head is 54 inches

high and mounts a 42-inch long declination shaft. With the declination axis

level and the tube upright, the instrument stands 8 feet tall. A new direction Since its departure from

Calver’s workshop more than a century ago this outstanding example of

the work of one of the leading instrument makers of the nineteenth and early

twentieth century has resided with four members of the Association –

three of them recipients of the Walter Goodacre Award. However, in June 2005

it crossed the country again, and in the care of John Armitage (a

longstanding member of the Association) it will continue its career in the

grounds of the adult education centre at Pendrell Hall, Staffordshire. At the

same time, John Armitage also took delivery of a 7-inch f/11 Calver

(instrument no. 150), to be installed in an observatory at the Black Country

Museum in Dudley. Both of these instruments will be used not only for private

work by amateur astronomers, but also for public education in science and

history. The 7-inch was presented to the Association by C. L. Lyons in 1952,

and nothing else is known of its provenance except its maker; but the

12¼-inch will be accompanied by an exhibition of its history,

detailing its significant role in the work of the Association and in the

development of astronomy throughout the twentieth century. A reflection George Calver was born in 1834

– nineteen years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. King William IV

was the reigning monarch, John Herschel had recently arrived at the Cape of

Good Hope to carry out his survey of the southern skies, Halley’s comet

was fast approaching, the nature and distance of the stars was a mystery, and

no-one could satisfactorily explain the features seen during a total solar

eclipse. Neptune was discovered when Calver was twelve years old, and about

four years later, when he moved to Great Yarmouth, other more famous

characters took up residence on the beach there: the Peggotty family, in

Charles Dickens’ David

Copperfield (published in 1849–50). Phillips

acquired the 12¼-inch more than half a century later, after the end of

the Victorian era. Halley’s comet had almost completed another orbit,

and Albert Einstein had published his theory of Special Relativity. Two

decades later, Calver died five days after the British total solar eclipse of

29 June 1927. In the same year that the instrument left Headley, the Second

World War ended with a vigorous demonstration of nuclear power; by the time

that Heath took delivery of the instrument, Mariner 2 had flown by Venus; and

in the month that Steele reassembled the instrument the Cassini spacecraft

was launched. After

more than a century of use for observation and education, there is no doubt

that instrument no. 93 has served astronomy more than any other instrument in

the Association’s collection, and that it will continue to maintain its

record of service for many years to come. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the Rev D.

Wotton, rector of Headley, and Peter Hingley, Librarian of the Royal

Astronomical Society, for permission to reproduce the photographs of

Phillips, Hargreaves and the Headley observatories; the latter for permission

to reproduce the photograph of Calver; Dr R. F. Griffin, for permission to

reproduce the photograph of F. M. Holborn; A. W. Heath, for information about

his stewardship of the instrument; R. M. Steele, for supplying details of the

instrument’s specifications; and Lesley Steele, David Kendall, Steve

Fletcher, Peter Drew, Jon Owen, and others, for considerable help with

refurbishment in 1997. The handling and transportation of such an instrument

is not a simple task (and can be dangerous), and sincere thanks are due to

Glyn Marsh, who in 2005 travelled from Lancashire to move the instrument from

Yorkshire to Staffordshire. Notes and references |

|||||||

|

1 |

Inches, as originally specified, are quoted throughout. |

||||||

|

2 |

For an account of the advent of silver-on-glass mirrors,

including the work of Henry Cooper Key, George Henry With, George Calver and

John Browning, see Marriott R. A., ‘The life and legacy of G.

H. With, 1827–1904’, J.

Brit. Astron. Assoc., 106 (1996), 257–64, and Marriott R. A.,

‘Webb’s telescopes’, in Robinson M. and J. H. (eds.), The Stargazer: The Life and Astronomy of Thomas William Webb

(Gracewing, Leominster, 2006). |

||||||

|

3 |

Since 1918 the Association has acquired ten instruments by

Calver: no. 33, 8½-inch (1918); no. 51, 6½-inch (1934); no. 93,

12¼-inch (1945), the subject of this paper; no. 99, 10-inch (1947),

which since 1986 has been on loan to J. H. Rogers, current Director of the

Jupiter Section; no. 122, 10-inch (1948), which from 1949 to 1988 was on loan

to W. E. Fox, Director of the Jupiter Section 1957–88; no. 129, 10-inch

(1949); no. 150, 7-inch (1952); no. 189, 6½-inch (1956), originally

owned by A. Stanley Williams (see ref. 11); no. 271, 10-inch (1967); and no.

337, parts of a mount (1980). |

||||||

|

4 |

A short obituary of Calver (in which the anonymous writer

mistakenly states that he was born in Great Yarmouth) was

published in Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 88 (1927), 251–2, but no

obituary was published in the Association’s Journal, nor in The

Observatory. |

||||||

|

5 |

Horace Edward Stafford Dall (1901–1986).

Dall’s 8½-inch Calver was made in 1877. He acquired it from

William Porthouse in 1920, and in turn, Porthouse had acquired it from Nathaniel

E. Green. The Horace Dall Medal and Gift was instituted in 1988; see Marriott

R. A., ‘The Association’s awards and medals’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 110 (2000),

29–37. |

||||||

|

6 |

Dall H. E. S., ‘George

Calver: East Anglian telescope maker’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 86 (1975), 49–52. The site of

Calver’s works is now a builder’s yard. |

||||||

|

7 |

Coleman W., ‘Micrometrical measures of double

stars’, Mem. R.

Astron. Soc., 51 (1899); 54 (1904). |

||||||

|

8 |

The 18-inch mirror (instrument no. 3) was made by G. H.

With in 1877, and was presented to the Association by Nathaniel E. Green in

1897 (see ref. 2). |

||||||

|

9 |

R. L. Waterfield joined the Association in 1914, served as

Director of the Mars Section 1931–42 and President 1954–56, and

was recipient of the Royal Astronomical Society’s Hannah Jackson

(née Gwilt) Gift and Medal in 1942 and the Associations’s Walter

Goodacre Award in 1966. For a detailed account of his life and work, see

Ridley H. B., ‘Appreciation of R. L. Waterfield’s 70 years of

membership’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 95 (1985), 174, and Hendrie M. J., ‘Reginald Lawson

Waterfield, 1900–86’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 97 (1987), 211–14. |

||||||

|

10 |

Worthington J. H. ‘Invitation

to Four Marks Observatory’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 25 (1914) 49–50. For an

account of Waterfield’s observations, see Moseley R. C. and Buczynski,

D. G., ‘R. L. Waterfield and Four Marks Observatory’, J. Brit.

Astron. Assoc., 98 (1988),

164–5. |

||||||

|

11 |

Arthur Stanley Williams (1861–1938) was an Original

Member of the Association, a member of the Provisional Committee, and a

member of Council 1890–93. He introduced transit timings of jovian features,

enabling detailed monitoring of longitudes and currents, and assigned the

names of the belts and zones. All of his early observations in the 1880s

– published in his Zenographical

Fragments – were made with a 6½-inch Calver. This instrument

was bequeathed to the Royal Astronomical Society in 1938, and was presented

to the Association in 1956 (instrument no. 189). It was placed on loan, but

in 1976 the borrower could not be traced. Williams also devoted much of his

time to the study of variable stars, of which he discovered many by

photography. In 1923 he was awarded the Royal Astronomical Society’s

Hannah Jackson (née Gwilt) Gift and Medal. |

||||||

|

12 |

Jupiter Section Memoirs

nos. 10–29 (1904–39): 12(3), 1904; 14(3), 1906; 16(1), 1908; 16(2),

1909; 16(3), 1910; 17(4), 1911; 19(3), 1913; 20(1), 1915; 21(1), 1917; 23(3),

1921; 24(2), 1923; 26(3), 1925; 26(4), 1926; 27(4), 1927; 29(1), 1929; 29(3),

1930; 30(2), 1932; 30(4), 1935; 32(4), 1937; 34(2), 1939. |

||||||

|

13 |

Many Saturn Section reports have appeared in the Journal, but only two Memoirs have been published – by

Nathaniel E. Green in 1893, and by George M. Seabroke in 1901. |

||||||

|

14 |

Phillips T. E. R., ‘Micrometrical measures of double

stars’, Mon.

Not. R. Astron. Soc., 71 (1911), 216; 72 (1912), 705; 73 (1913), 159; 75 (1915),

434; 76 (1916), 655; 77 (1917), 624; 78 (1918), 477; 79 (1919), 509; 80

(1920), 643; 81 (1921), 566; 84 (1924), 776; 86 (1926), 77; 88 (1928), 183;

91 (1931), 238; 95 (1935), 186; 98 (1938), 88; 101 (1941), 48. |

||||||

|

15 |

For Waterfield’s

illustrated account of his observatory and instruments at Headley in 1941,

see J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 51

(1941), 138. |

||||||

|

16 |

The Walter Goodacre Award was instituted in 1929 (see ref.

5, op. cit.). |

||||||

|

17 |

Peek B. M., obituary of T. E.

R. Phillips, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc.,

52 (1942),

203–8; also Steavenson W. H., obituary of T. E. R. Phillips, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 103 (1934), 70–2. After

Phillips received his DSc, Martin Davidson published a short account of his

work in the May 1942 issue of The

Observatory, 64 (1942), 228. This was the month in which

Phillips died; consequently, no formal obituary was published. |

||||||

|

18 |

The Hudson refractor (instrument no. 94) was later loaned to

P. L. Pyer (1963–64), B. C. Hellyer (1964–69) and M. V. Gavin

(1979–99), and is now in the care of the Curator of Instruments. |

||||||

|

19 |

In 1968 Waterfield moved to Woolston, near Wincanton, Somerset.

In 1986 he bequeathed the 6-inch Cooke refractor and its accompanying

photographic lenses to Michael J. Hendrie; see Hendrie M. J., ‘A

run-off roof observatory’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 104 (1994), 300–3. In summer 2005, Hendrie presented

the instrument to Dr R. J. McKim, Director of the BAA Mars Section. |

||||||

|

20 |

Welsh H., ‘Port Elizabeth Observatory’, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 68 (1957), 34–5. Henry

Welsh joined the BAA in 1928, and observations made with the 8-inch Cooke at

Port Elizabeth were submitted to several of the Sections. |

||||||

|

21 |

Patston G. E., obituary of F. M. Holborn, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 72 (1962),

406–8. |

||||||

|

22 |

For Holborn’s illustrated account of his observatory

and instruments in 1940, see J. Brit. Astron.

Assoc., 50 (1940), 339–40. |

||||||

|

23 |

Waterfield, R. L. and Holborn

F. M., ‘Memorial to the late T. E. R. Phillips, J. Brit. Astron. Assoc., 58 (1947),

218. |

||||||

|

24 |

After being loaned to several members, the 5-inch Ross

refractor (instrument no. 237) was sold to S. J. Anderson in 1997, and now

resides in Cornwall. |

||||||